In this video, Philip Roberts clears up a lot of the details surrounding JavaScript’s call stack, callback queue, and event loop. Feel free to skip this blog post and spend a half hour watching the video instead. But if you’d rather skim my highlights, don’t let me stop you!

What is JavaScript

What is JavaScript anyway? Some words:

- It’s a single-threaded, non-blocking, asynchronous, concurrent language”

- It has a call stack, an event loop, a callback queue, some other apis and stuff

If you’re like me (or Philip Roberts, it seems), these words themselves don’t mean a ton. So let’s parse that out.

JavaScript Runtimes

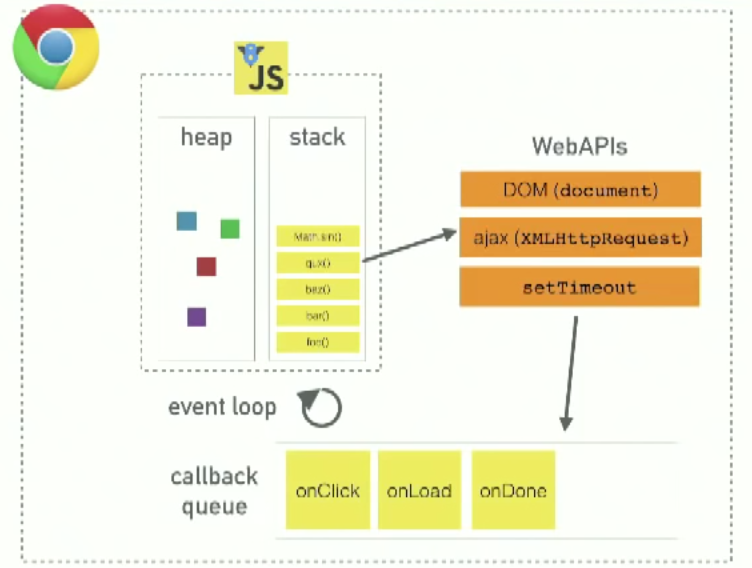

JavaScript runtimes (like V8) have a heap (memory allocation) and stack (execution contexts). But they don’t have setTimeout, the DOM, etc. Those are web APIs in the browser.

JavaScript as we know it

JavaScript in the browser has:

- a runtime like V8 (heap/stack)

- Web APIs that the browser provides, like the DOM, ajax, and

setTimeout - a callback queue for events with callbacks like

onClick,onLoad,onDone - an event loop

What’s the call stack?

JavaScript is single-threaded, meaning it has a single call stack, meaning it can do one thing at a time. The call stack is basically a data structure which records where in the program we are. If we step into a function, we push something onto the stack. If we return from a function, we pop off the top of the stack.

When our program throws an error, we see the call stack in the console. We see the state of the stack (which functions have been called) when that error happened.

Blocking

An important question that this relates to: what happens when things are slow? In other words, blocking. Blocking doesn’t have a strict definition; really it’s just things that are slow. console.log isn’t slow, but while loops from 1 to 1,000,000,000, image processing, or network requests are slow. Those things that are slow and on the stack are blocking.

Since JS is single-threaded, we make a network request and have to wait until it’s done. This is a problem in the browser—while we wait on a request, the browser is blocked (can’t click things, submit forms, etc.). The solution is asynchronous callbacks.

Concurrency, where we realize there’s a lie above

It’s a lie that JavaScript can only do one thing at a time. It’s true: JavaScript the runtime can only do one thing at a time. It can’t make an ajax request while doing other code. It can’t do a setTimeout while doing other code. But we can do things concurrently, because the browser is more than the runtime (remember the grainy image above).

The stack can put things into web APIs, which (when done) push callbacks onto task queue, and then…the event loop. Finally we get to the event loop. It’s the simplest little piece in this equation, and it has one very simple job. Look at the stack and look at the task queue; if the stack is empty, it takes the first thing off of the queue and pushes it onto the stack (back in JS land, back inside V8).

Louping it all together

Philip built an awesome tool to visualize all of this, called Loupe. It’s a tool that can visualize the JavaScript runtime at runtime.

Let’s use it to look at a simple example: logging a few things to the console, with one console.log happening asynchronously in a setTimeout.

What’s actually happening here? Let’s go through it:

- We step into the

console.log('Hi');function, so it’s pushed onto the call stack. console.log('Hi');returns, so it’s popped off the top of the stack.- We step into the

setTimeoutfunction, so it’s pushed onto the call stack. setTimeoutis part of the web API, so the web API handles that and times out the 2 seconds.- We continue our script, stepping into the

console.log('Everybody')function, pushing it onto the stack. console.log('Everybody')returns, so it’s popped off the stack.- The 2-second timeout completes, so the callback moves to the callback queue.

- The event loop checks if the call stack is empty. If it were not empty, it would wait. Because it is empty, the callback is pushed onto the call stack.

console.log('Everybody')returns, so it’s popped off the call stack.

An interesting aside: setTimeout(function(...), 0). setTimeout with 0 isn’t necessarily intuitive, except when considered in the context of call stack and event loop. It basically defers something until the stack is clear.

Considering UI render performance

To this back to something more surface level, something we deal with every day, let’s consider rendering. The browser is constrained by what we’re doing in JavaScript. It would like to repaint the screen every 16.6ms (or 60 frames/second). But it can’t actually do a render if there’s code on the stack.

As Philip says,

When people say “don’t block the event loop”, this is exactly what they’re talking about. Don’t put slow code on the stack because, when you do that, the browser can’t do what it needs to do, like create a nice fluid UI.

So, for example, scroll handlers trigger a lot and can cause a lagging UI. Incidentally, this is the clearest explanation I’ve heard of debouncing, which is exactly what you need to do to prevent blocking the event loop (that is, let’s only do those slow events every X times the scroll handler triggers).

Closing

In summary, that’s what the heck the event loop is. Philip’s talk helped me understand a lot of what JavaScript is, what it isn’t, which parts of it are runtime vs. browser, and how to use it effectively. Give the talk a watch!